Judge the Publishing Industry by Its Covers

In her third Stella Schools Blog guest post, writer and reviewer Danielle Binks suggests that rather than judging a book by a gendered or sexist cover, it is the publishing industry that should be standing trial.

In recent years the likes of the Stella Prize and VIDA: Women in Literary Arts have illuminated some of the ways men still dominate the literary world, publishing irrefutable evidence of disparities in review coverage of male and female authors. This underrepresentation in reviewing contributes to a broader cultural devaluation of women’s writing, something that also manifests on literary award shortlists, which are more likely to feature male authors than female authors. It’s even been shown that male-centric stories written by women are more likely to win them awards than female-centric ones. All of this has resulted in female authors speaking up with increasing frequency about their frustration with the industry.

An equally important subject, but one that’s often given less weight in this discussion, is that of aesthetics. Before they even hit bookshop shelves, books written by women are often subtly positioned as inferior to those by men through their cover design.

‘It’s one of the best-known facts in book publishing, that women buy and read many more books than men,’ says James Morrison, an editor and designer who writes sporadically about book design at Caustic Cover Critic. ‘Almost every marketing decision in the publishing world seems to be made in spite of the female readership, rather than with it in mind.’

Some of the cover choices that result from these marketing decisions are more subtle than others, but still insidious in their subjugation of women’s voices. For instance: ‘if you are publishing a serious book and you want to have a critic’s quote on the front, it’s almost certainly going to be a quote from a man,’ Morrison says.

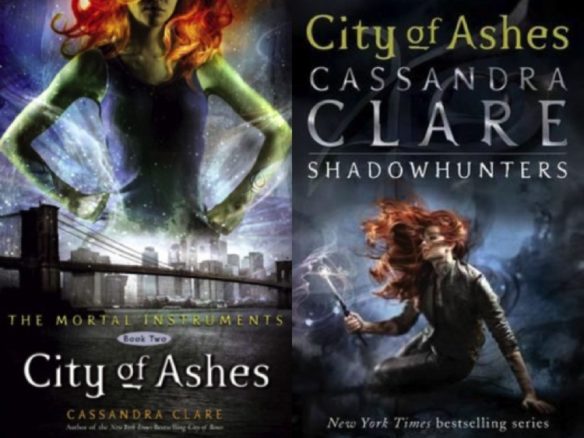

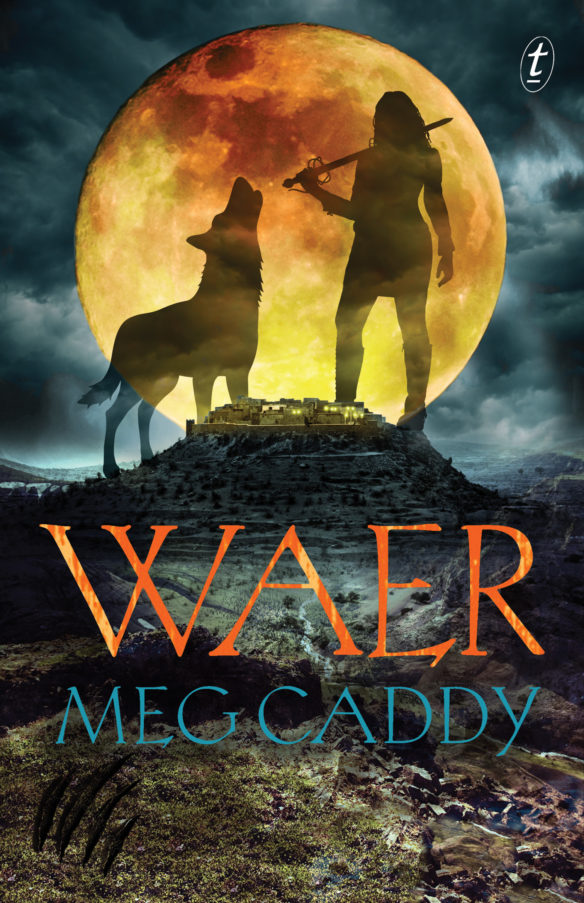

One area of publishing where Morrison has seen some improvement is in Young Adult (YA) books, particularly YA fantasy cover art: ‘Here you find an array of strong female characters represented on the covers wearing all of their clothes and generally wielding swords or other weapons, facing the reader directly and looking very much not to be messed with. [See recent books by Isobelle Carmody, Sarah J. Maas and Richelle Mead as examples.] These demonstrate that you don’t have to be coy just because your book is about female characters, that you don’t have to be frightened about showing specific individuals on a cover and that you don’t have to pander to some hypothetical male gaze to sell books.’

One area of publishing where Morrison has seen some improvement is in Young Adult (YA) books, particularly YA fantasy cover art: ‘Here you find an array of strong female characters represented on the covers wearing all of their clothes and generally wielding swords or other weapons, facing the reader directly and looking very much not to be messed with. [See recent books by Isobelle Carmody, Sarah J. Maas and Richelle Mead as examples.] These demonstrate that you don’t have to be coy just because your book is about female characters, that you don’t have to be frightened about showing specific individuals on a cover and that you don’t have to pander to some hypothetical male gaze to sell books.’

Any improvements in YA book covers have been hard won, and came after authors and readers spoke up about their disdain for gendered marketing.

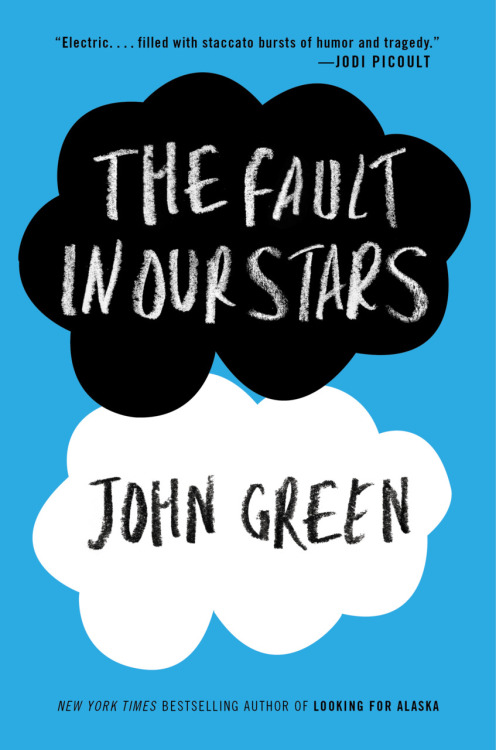

In a 2013 Tumblr post, American YA author John Green reflected on the phenomenal success of The Fault in Our Stars, his 2012 novel about two love-struck teenagers dying of cancer. In the post, Green addressed some presumptions around the success of his book, in particular the aesthetics of his book cover. It had often been suggested, he wrote, that ‘The Fault in Our Stars got a cool, literary cover because I’m a guy, and if I’d been female it would’ve had a pink cover with a decapitated girl head.’ He added, ‘And it might have, if I’d been a female first novelist with someone other than Julie Strauss-Gabel as my editor.’

The Fault in Our Stars did indeed get a cool, literary cover. It was designed by Rodrigo Corral, who has also designed covers for Lauren Groff, Jeffrey Eugenides and Junot Díaz, but has not, from what I can see, designed any other YA covers before or since working with Green. It’s also worth noting that when Green was a debut YA novelist, his book Looking for Alaska, another story about young love, got another cool, literary, gender-nonspecific cover.

The Fault in Our Stars did indeed get a cool, literary cover. It was designed by Rodrigo Corral, who has also designed covers for Lauren Groff, Jeffrey Eugenides and Junot Díaz, but has not, from what I can see, designed any other YA covers before or since working with Green. It’s also worth noting that when Green was a debut YA novelist, his book Looking for Alaska, another story about young love, got another cool, literary, gender-nonspecific cover.

Although Green’s books were untouched by the ‘pink cover with a decapitated girl[’s] head’ phenomenon, this cover trend provoked a heated online debate around the time of his post. Young book bloggers pointed to the submissiveness of female heroines, particularly on YA paranormal and fantasy book covers, and to the trend of ‘headless heroines’ (models with their heads cropped off) on YA covers in all genres, but mostly on books written by female authors.

American YA author Maureen Johnson wrote a Huffington Post editorial on the issue, expressing her frustration with the disparity between covers for male and female YA authors’ books. Johnson suggested a ‘coverflip’ challenge, subverting traditional ‘feminine’ covers. She said: ‘The simple fact of the matter is, if you are a female author, you are much more likely to get the package that suggests the book is of a lower perceived quality.’ Not even famous female literary icons were immune from the trend of gendered book covers – in 2013 another furore arose over the chick-lit-esque cover of a new edition of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar.

Though there is another dimension to this discussion: are neutral book covers in fact another way for readers to reject the feminine? It’s often said that girls will read anything, but boys will only read ‘boy books’, so does neutralising book covers do a disservice to young (mostly male) readers, by reinforcing this idea that they shouldn’t have to read anything that purports to be outwardly feminine, which is essentially telling them that they don’t have to read about anyone who doesn’t look just like them?

Whatever the case may be, Johnson believed that the decision and push for change should come from readers: that theirs was the most important opinion in such matters. Back in 2013, Johnson addressed readers directly, saying: ‘If you don’t like the cover, take it off or make a new one! It’s YOUR BOOK. Also, write to/tweet at publishers and TELL THEM what you think!’

When these sorts of discussions take place, the phrase ‘Don’t judge a book by its cover’ inevitably comes to mind. How ironic that it is generally agreed to have been coined by author Mary Ann Evans, who wrote under the masculine pen name George Eliot in order to ensure her works would be taken seriously.

Perhaps we should heed another Eliot quote: ‘What a different result one gets by changing the metaphor!’ Do let’s judge poorly conceived book covers, as Maureen Johnson suggests, but let’s also tell publishers what we think of their gendered marketing. And instead of judging a writer by her cover, let’s judge the industry that recycles the same reductive clichés.