Writing the Wrongs of Stereotypes

Recently we have seen a renewed increase in bigotry, fear and Islamophobia in Australia, across the political sphere and the media, and among some leading political and social commentators.

We believe there are more powerful views in our community – of solidarity, inclusivity and empowerment.

In our new series, Pushback: Writers Respond To Bigotry, the Stella Schools blog is offering an alternative platform for contributions from constructive and positive voices. A series of guest writers will address topics related to culture, gender, diversity and representation.

In our latest post, Stella Schools Ambassador Sarah Ayoub argues that our ability to see one another clearly is restricted by stereotypes – and that Australian young adult fiction is fighting back, providing more diverse stories for a new generation.

Writing the Wrongs of Stereotypes

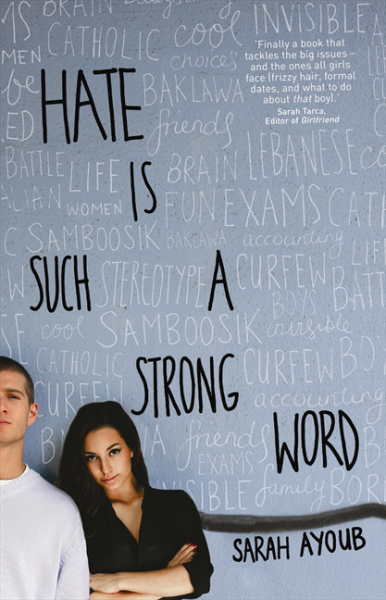

A few weeks ago, during an interview about my novels, I was posed a question that caught me off guard. It was about the main character of my debut novel, Hate Is Such a Strong Word, specifically the fact that she was Lebanese Christian. The interviewer wanted to know if I had just made her up, or if Lebanese Christians were, as she put it, ‘an actual people group’.

A few weeks ago, during an interview about my novels, I was posed a question that caught me off guard. It was about the main character of my debut novel, Hate Is Such a Strong Word, specifically the fact that she was Lebanese Christian. The interviewer wanted to know if I had just made her up, or if Lebanese Christians were, as she put it, ‘an actual people group’.

Maybe that question hit too close to home, but I’m still recovering from the shock of it. The fact that this ‘people group’ didn’t exist in her world seemed a great tragedy to me.

A couple of months ago, a veiled Muslim woman on a beach in Nice was fined and forced by French police to remove her burqini in public, for daring to defy a ban on the wearing of religious garments that compromise France’s ‘secularism’ and ‘liberty’.

I can’t stop thinking about this woman. It was with a heavy heart that I chose not to look at the photos of her; I didn’t want to be another witness to this act of humiliation. I didn’t want to be another set of eyes looking at her body, which she chose to cover up and which society – by virtue of its idea of ‘freedom’ – forced her to bare. Banning a garment that allows women the freedom to enjoy something so universal as the ocean is mind-boggling.

It’s steeped in the kind of ignorance that assumes that the hijab is forced on a woman. In many ways, a ban that takes away a woman’s right to choose how she wears her clothes is no better than that assumption. It leads to the kind of fear of difference that, in Australia, has seen Pauline Hanson call for CCTV in all mosques or for a blanket ban on Muslim immigration. A fear, reinforced by media and political biases, that makes whole groups of people invisible while demonising others – all the while failing to acknowledge the diversity within those communities themselves.

In our current climate, our moral compasses are driven by so much more than black and white, and stereotyping is at the heart of our approach to social behaviour. When we stereotype people of faiths, colours and orientations that are different from our own, we fail to see them as individuals. We see them instead as collective representations of an ‘otherness’ that we’re fed by the press, politics and popular culture. These stereotypes are perpetuated in the far-too-common narratives that saturate society and are a product of the lack of diversity in our public landscape.

Only in art and culture can we rid ourselves of the stereotypes that we both experience and replicate. In photography and video, through poetry slams and literature, marginalised voices are owning their experiences and offering up a different view to that of the mainstream.

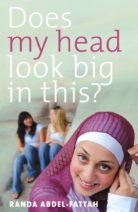

Australian young adult fiction is encouraging future generations to see people as they really are – as individuals. Authors such as Randa Abdel-Fattah, whose character Amal in Does My Head Look Big in This? fights for her decision to wear the hijab (to the horror of her parents!), and Erin Gough, whose character Delilah in The Flywheel doesn’t feel the need to shy away from her sexuality, counter stereotypes by creating real, flawed, lovable characters who want to be seen as individuals, rather than be defined by their race, ethnicity or sexuality. There are more: Kirsty Eagar addresses sexual shaming through Jess in Summer Skin; Kylie Fornasier writes about invisible disability with her character Piper in The Things I Didn’t Say; Tamar Chnorhokian’s character Zara grapples with body image in The Diet Starts on Monday. All of these stories, and more, feature characters we might sit next to on the train, but not really consider ‘actual people’.

Australian young adult fiction is encouraging future generations to see people as they really are – as individuals. Authors such as Randa Abdel-Fattah, whose character Amal in Does My Head Look Big in This? fights for her decision to wear the hijab (to the horror of her parents!), and Erin Gough, whose character Delilah in The Flywheel doesn’t feel the need to shy away from her sexuality, counter stereotypes by creating real, flawed, lovable characters who want to be seen as individuals, rather than be defined by their race, ethnicity or sexuality. There are more: Kirsty Eagar addresses sexual shaming through Jess in Summer Skin; Kylie Fornasier writes about invisible disability with her character Piper in The Things I Didn’t Say; Tamar Chnorhokian’s character Zara grapples with body image in The Diet Starts on Monday. All of these stories, and more, feature characters we might sit next to on the train, but not really consider ‘actual people’.

When these books make it into the hands of young readers who might not personally encounter marginalised groups, they do a lot more than tell stories: they foster a sense of empathy, and an understanding of difference and the struggles and joy that come with it. Young adult fiction is read and loved by people of all ages but, importantly, it puts positive messages into the hands of those who may someday take up positions in the corporate world, in politics, or in not-for-profits – young people who will have a positive impact on our society.

Authors derive a sense of creativity and freedom from the act of writing – we write outside the confines of our daily lives and create alternative realities different from our own. Sometimes they’re utopian; at other times they help us identify wrongs so that we can make them right. In reading, our audiences gain new perspectives and a deeper understanding of the world around them.

Sarah Ayoub is a journalist and author of YA fiction. Her novels Hate Is Such a Strong Word and The Yearbook Committee are contemporary stories of identity, belonging and discovery. She is also a Stella Schools Ambassador.

Sarah Ayoub is a journalist and author of YA fiction. Her novels Hate Is Such a Strong Word and The Yearbook Committee are contemporary stories of identity, belonging and discovery. She is also a Stella Schools Ambassador.