Women’s Bodies in Speculative Fiction

For her fourth Stella Schools Blog guest post, writer and reviewer Danielle Binks speaks with YA authors about the representation of women characters in fantasy YA, and how they approach the issue in their own work.

Within contemporary young adult literature, there has been a push for more body diversity – particularly of female characters. Australian YA author Melissa Keil wrote for the Guardian earlier this year: ‘For young people, at a time in their lives that can be isolating, and fraught with questions of body image, sexuality and identity, this representation can be vital.’ There have been a few stellar examples of positive fat representation in contemporary YA recently, such as Julie Murphy’s self-proclaimed fat girl, Willowdean Dickson, who decides to enter a beauty pageant in Dumplin’. Murphy’s book is being praised by many for putting positive fat bodies on the page, and is just one of many contemporary YA books offering more varied portrayals of women’s bodies.

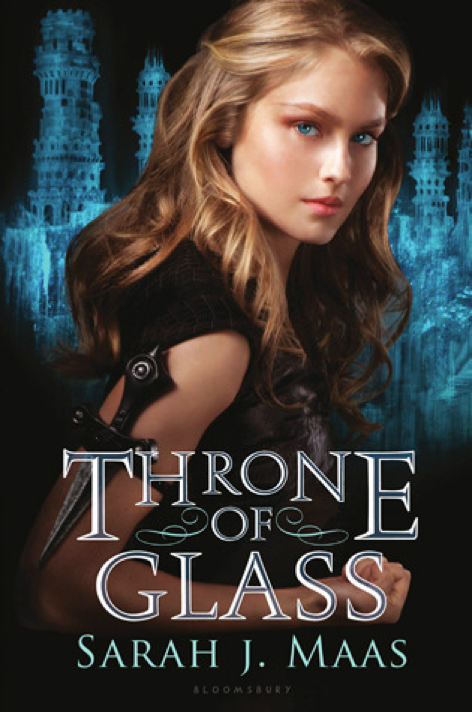

But within the fantasy YA genre, it’s a different story – one in which Western beauty standards of tall, lithe and blonde heroines still reigns supreme. Like Celaena Sardothien in Sarah J Maas’ popular Throne of Glass fantasy series, who is described as having ‘long, blonde hair’ and eyes ‘bright blue and ringed with gold.’ Sarah J Maas repeats this physicality in her latest YA fantasy series, A Court of Thorns and Roses, featuring protagonist Feyre Archeron: tall and slender, with pale skin, golden-brown hair and slightly up-tilted blue-grey eyes.

But within the fantasy YA genre, it’s a different story – one in which Western beauty standards of tall, lithe and blonde heroines still reigns supreme. Like Celaena Sardothien in Sarah J Maas’ popular Throne of Glass fantasy series, who is described as having ‘long, blonde hair’ and eyes ‘bright blue and ringed with gold.’ Sarah J Maas repeats this physicality in her latest YA fantasy series, A Court of Thorns and Roses, featuring protagonist Feyre Archeron: tall and slender, with pale skin, golden-brown hair and slightly up-tilted blue-grey eyes.

American aphorist Mason Cooley once said, ‘Fantasy mirrors desire. Imagination reshapes it.’ How is it that even in speculative-fiction genres – ones with no imaginary bounds – women’s bodies tend to be filtered through the modern male gaze with narrow standards of Western beauty?

‘Fantasy writers proudly say they’re not limited by reality, that their imagination can go anywhere – but they tend to default to beauty/power stereotypes in female characters,’ agrees Australian YA spec-fic author Michael Pryor. ‘We seem to be happy to accept ugly males with great power. This might be through writers notionally tipping the hat to history where many powerful men were hideous – the Habsburg lip, anyone? – but again I don’t think many writers think too deeply about this. It’s simply accepted that men don’t have to be attractive to be powerful.’

Pryor believes such repetitive portrayals is in part due to writers falling for ‘Epic Writing Mode’, where ‘all aspects of a character must match the awesome scale of the story. Qualities such as intelligence, strength, goodness/badness and power are all dialled up to the max – and so, accordingly, is beauty. It’s a shame, as it can be a writer shortcut, a decision made without realising we make it, and as such we end up with defaults rather than challenging the stereotype.’

These stereotypical characters are certainly what Australian author Melina Marchetta read growing up, and what she wanted to challenge in her own epic fantasy trilogy, The Lumatere Chronicles. ‘In most of the stories I grew up with, beautiful princesses or queens were both guided and saved by brave men,’ says Marchetta. ‘These days, the female protagonists do the guiding and saving, but they’re still beautiful. When I wrote the character of Evanjalin, in Finnikin of the Rock, I was determined not to go down the path of a beautiful girl encouraging an army of world-weary people into following her to their rightful home. … What I wanted was to create a character who deserved the power to lead a kingdom, but through her actions (not action), grit and craftiness.’

Another aspect of writing women’s bodies that needs to shift in fantasy – young adult fantasy in particular – is the urge to write to Western idealised beauty standards. As Marchetta explains of her character Evanjalin in The Lumatere Chronicles: ‘I knew she would have the colouring of someone described in our world as Mediterranean or Middle Eastern, because I grew up surrounded by people who were southern Italian, Greek and Lebanese, and the way we looked was, and still is, pretty much absent from many of the fantasy novels I’ve read. But there lay another challenge, because the few female characters I’ve encountered in novels, who aren’t white Anglo or Celtic Western types, were romanticised as being exotic or foreign beauties.’

For some characters, physical description doesn’t play into their stories at all, like Australian YA author Ambelin Kwaymullina’s female protagonists: ‘The Tribe series is, in the end, the story of three girls: Ash, Ember and Georgie,’ says Kwaymullina. ‘There’s no way of knowing if any of the three girls are beautiful, because they none of them ever think about it, and none of them are ever described in terms of their physical attractiveness. Also, they’re not anywhere close to perfect, which is why their friendship is so important, because they complement each other’s strengths and compensate for each other’s weaknesses. Ash acknowledges throughout the whole of the story that Ember is smarter than she is; Ember can’t bring people together the way Ash can; and Georgie sees further than them both but has trouble orientating herself in the present moment.’

This is something Michael Pryor is thinking about in his writing too. ‘I’m also avoiding characters commenting on each other’s gorgeousness, either in dialogue or in thoughts. I’m aiming for characters accepting characters and looking past skin-deep details,’ he says.

Marchetta has also been moved to question the very need that readers have for barometers of beauty in her characters. ‘I was reminded often when reading reviews of Froi of the Exiles that we’re trained to want our princesses beautiful, because only the beautiful can worm their way into a reader’s heart,’ she notes. ‘I was often disheartened when readers couldn’t deal with Quintana’s appearance, and didn’t think she was worthy of her place as the heroine in a novel. But then again, Evanjalin received worse criticism because she dared to be cunning. What I hope I do with the construct of my female characters is challenge readers not to take them on face value. Phaedra, Celie, and Quintana possess some amazing traits that have little to do with physical beauty, and much to do with tenacity, empathy and courage.’

Marchetta has also been moved to question the very need that readers have for barometers of beauty in her characters. ‘I was reminded often when reading reviews of Froi of the Exiles that we’re trained to want our princesses beautiful, because only the beautiful can worm their way into a reader’s heart,’ she notes. ‘I was often disheartened when readers couldn’t deal with Quintana’s appearance, and didn’t think she was worthy of her place as the heroine in a novel. But then again, Evanjalin received worse criticism because she dared to be cunning. What I hope I do with the construct of my female characters is challenge readers not to take them on face value. Phaedra, Celie, and Quintana possess some amazing traits that have little to do with physical beauty, and much to do with tenacity, empathy and courage.’

Across all genres in books, TV, film, comic books and video games, the representations of women’s bodies need to better reflect truth, honesty and diversity, not narrow definitions of beauty. Fantasy, perhaps more than any other genre, has the most powerful literary weapons in its arsenal – writers are quite literally creating new worlds and new world orders to suit their fantastical purposes. Yet, all too often, fantasy writers fall back on old stereotypes and tired tropes that bind women’s attractiveness to their worth.

Some authors are actively working to subvert these female archetypes in their fantasy novels, but those tropes will persist so long as readers accept them – even in the most far-out fantastical realms. If we start demanding diverse female characters, then maybe we will see a break away from modern standards policing women’s bodies, and embrace the opportunity to show that great power can come from anywhere.

Danielle recommends:

- The Lumatere Chronicles trilogy by Melina Marchetta

- The Lotus War series by Jay Kristoff

- The Tribe series by Ambelin Kwaymullina

- The Reformed Vampire Support Group by Catherine Jinks

- Shadowshaper by Daniel José Older

- Nimona graphic novel by Noelle Stevenson

- Faith comic book series by Jody Houser

- Fire and Thorns trilogy by Rae Carson

- An Ember in the Ashes series by Sabaa Tahir

- Of Metal and Wishes series by Sarah Fine

- Akata Witch by Nnedi Okorafor

- Binti by Nnedi Okorafor

- NIOBE: She is Life by Amandla Stenberg, Sebastian A. Jones

- Uglies series by Scott Westerfeld

- Only Ever Yours by Louise O’Neill

- And I Darken by Kiersten White

- Dreadnought by April Daniels [2017 release]