Gender-flipping and Twilight

Danielle Binks is a writer and reviewer, with a particular interest in youth literature. She’ll be writing a series of guest posts on the Stella Schools Blog over the coming months, covering various issues facing women in YA.

Discussions about gender-flipping have occurred with some regularity over recent years in the American film industry, the source of so much of Australia’s cultural consumption. This year alone there has been much hype around Paul Feig’s upcoming all-female Ghostbusters, as well as Sandra Bullock’s role in Our Brand Is Crisis, which was originally written for George Clooney and based on a real Democratic campaign consultant, James Carville. In fact, Hollywood has had great gender-swapping successes in the past – perhaps the most famous example being Ellen Ripley, played by Sigourney Weaver in Ridley Scott’s Alien franchise – although the box-office success of those films hasn’t necessarily seen an improvement in the number or variety of roles available to women.

In the publishing industry, however, conversations about gender-flipping haven’t abounded in quite the same way; although narratives largely go uninterrogated, aesthetics have been put under the microscope. For instance, in the comic book realm, the online Hawkeye Initiative highlights the pervasiveness of the male gaze by drawing male superheroes in the same suggestive poses and scant outfits as their female counterparts. Another example is the discussion around gendered book covers sparked by American YA author Maureen Johnson in 2013, which sets out the challenge to “coverflip” the perceived “masculinity” or “girliness” of book covers.

This challenge hints at the fact that within the young adult readership, specifically, we are starting to see the topic of gender stereotypes arise more frequently, which, as well as Maureen Johnson, is certainly in part thanks to Stephenie Meyer.

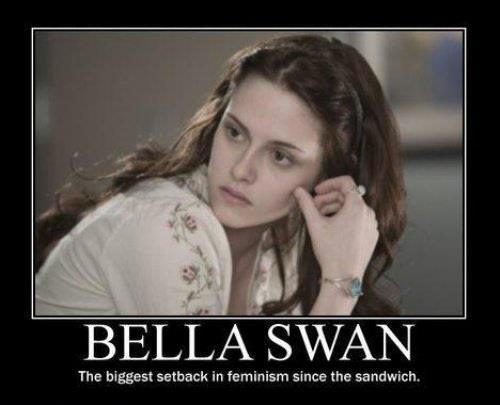

This meme, and so many others just like it, started making the rounds soon after the first book in Stephenie Meyer’s young adult Twilight saga became a publishing juggernaut back in 2005 (selling over 100 million copies in 37 translations). It’s no wonder, then, that in celebrating Twilight’s 10th anniversary Meyer has taken the opportunity to redress the anti-feminism label the books are often slapped with, by offering a gender-flipped version of Bella and Edward’s romance.

In bonus content released with the 10th anniversary edition, a story called Life and Death: Twilight Reimagined is included – with the characters changed to human boy Beau Swan, and his vampire crush Edythe Cullen.

Meyer says this gender-flipped version is her attempt to address criticisms that protagonist, Bella, is nothing more than a “typical damsel in distress”. Speaking to Good Morning America, Meyer said, “It’s always bothered me a little bit because anyone surrounded by superheroes is going to be in distress; we don’t have the powers … I thought, What if we switched it around a bit and see how a boy does? and, you know, it’s about the same.”

But those who’ve read it have said that Meyer’s Reimagined isn’t quite the subversive game-changer it could have been. Teo Bugbee, writing for The Daily Beast, points out that Beau is not plagued with the same monologue of self-doubts and insecurities that Bella was, suggesting that Meyer falls into writing the very gender norms she was trying to challenge.

This may be so, but perhaps what is worth celebrating is the fact that Meyer has put the topic of gender-flipping on the pop-culture agenda – and for teen readers no less – at a time when the literary community could demonstrate a greater level of self-awareness when it comes to subversive commentary such as this.

Australia is punching above its weight in this conversation, and the rumbles of change are not only coming from the United States. Bestselling Australian young adult author Amie Kaufman has also spoken frequently about how gender-flipping secondary characters has helped shape her writing.

“It came about originally as part of the process we go through after we’ve written the book,” explains Kaufman, who co-wrote the YA Starbound trilogy with American author Meagan Spooner. “We looked at each secondary character and asked ourselves: in terms of world-building, what is the message we want to convey with this character? Do we want to add to what we have here, subtract from it or change it?”

One of the characters Kaufman re-examined in edits of This Shattered World was a male corporal who, she says, “just happened to be written that way, because when we write these things originally we don’t make a lot of conscious choices about secondary characters until we know if the scene is going to stay in or not”. But upon closer examination, the pair decided that they wanted to make sure there were more rank and file soldiers who were women, so changed the corporal’s gender to female.

But, after gender-flipping the character, Kaufman reacted to her differently: “Re-reading that scene, there’s a moment when she steps forward to challenge … and I caught myself thinking, Oh geez, that’s a bit aggressive! Is that too aggressive? And I didn’t think that when she was a guy. So it was just a moment when that became visible to me that sparked a conversation of Let’s do that with all of our characters!”

Kaufman explains: “What’s interesting is that even those of us who are committed feminists carry around in our heads a lot of lessons that we were taught growing up that are invisible to us, and there’s always this urge to say Oh, no – I don’t have any problematic thoughts or instincts, because I’m a good feminist! But the thing is, of course you do – you were raised that way. And society reinforced it from day one. The good work in your feminism is actually making yourself aware of those thoughts and actions, and then consciously changing them … because what you do consciously does become habit.”

Kaufman now brings this process of gender flipping into everything she writes, but explains: “We don’t necessarily leave everybody flipped. For us the purpose is in checking whether or not we’ve written them in a gendered way … We may leave it as a male who has a softer approach, or we may have a female who steps up and behaves differently. Because it’s about creating a cast of characters who respond as humans, rather than responding with traditionally gendered behaviour.”

From a reader’s perspective, there’s certainly more power in a story that recognises the potential harm in those gendered norms and challenges them at the editing stage, rather than in an anniversary edition ten years later. And the more we talk about gendered writing and the logic behind gender-flipping, the more we’re asking readers to question their own preconceptions – a truly inspiring outcome when it emerges from authors having set that challenge for themselves .