The Stella Interview: Fiona Wright

Fiona Wright is shortlisted for the 2016 Stella Prize for her collection of essays, Small Acts of Disappearance: Essays on Hunger. We spoke to Fiona about writing fellowships, her favourite cafés and the people who inspire and influence her.

Stella: Which writers have shaped your work?

Fiona: There were a few specific writers whose work was really important to me while I was writing Small Acts of Disappearance – if I were to list those that have shaped my work as a whole we’d be here for hours! Joan Didion’s book The Year of Magical Thinking really helped me start thinking about form – about how it might be possible to write about experiences that don’t have a linear narrative, or don’t make sense in a linear way. Leslie Jamison’s The Empathy Exams, a book I really loved, and Sheila Heti’s How Should A Person Be? were really powerful examples of writing that blends the personal with larger narratives; with the political, with the outside world. Helen Garner, Beverley Farmer and Drusilla Modjeska do this wonderfully too, of course, and I’ve been reading their work for a very long time, so they influenced my essays as well.

Stella: Is there a writer you aspire to be like?

Fiona: Margaret Atwood, without question, for her fierce wit, finely tuned bullshit-meter and her willingness to call people out on their assumptions. In my favourite story about her, she tells a man at a party that she’s a novelist and he says something along the lines of: ‘How lovely, I’ve always thought that I would write a novel once I retire.’ Then, when he mentions that he’s a surgeon, she responds: ‘How lovely, I’ve always though I’d do some surgery once I retire.’ As a writer, too, she’s passionate and political and sensual at the same time, and her female characters are complex and often cruel, if only in their thoughts, which I really love to see.

Stella: Why did you become a writer?

Fiona: It sounds really twee to say this, but I don’t think I ever really had any choice. I’ve always written – stories and letters and little poems – even before I really recognised what I was doing. I’ve always loved books – I have really strong memories of reading in my bedroom as a child while my siblings were playing in the yard or watching movies. As an adult, I know that writing is the one solid means I’ve always had to sort through experiences, of making sense of my life; every time I’ve been kept from it, for whatever reason, I’ve felt deeply unsettled and somehow disorganised. I really love writing, I love my job and I know how lucky I am to be able to say that. There is quite literally nothing that I would rather do.

Stella: Do you have a good writing place?

Fiona: I love to write in cafés, especially big and airy cafés, and I have three or four within a short walk of my house in which I write so often that when I turn up now, they bring me my order without even asking. I love this ritual and the sense of being out in the world, in public, whilst still being entirely engaged in the very private world of writing and thinking. I love watching and listening to the people at nearby tables, especially when I catch snippets of the stories that they’re telling each other. I work mostly from home, so I also think it’s important to make sure I get out and into a different space for a few hours each day – it can be too isolating otherwise.

Stella: Have you ever received a grant, residency or fellowship to write?

Fiona: I have been fortunate enough to receive a few residencies over the years that I’ve been writing. The first was when I was very young – 24 years old, I think – and it was with the Tasmanian Writers’ Centre, in their beautiful, nineteenth-century writers’ cottage, which is perched on a hill directly above the Salamanca Markets and looks out to the mountain and the river from each side. That residency was incredibly important to me: it was the first time I’d been sent somewhere, given a place to stay and a small stipend, in order to do nothing else but write. It was the first time, I felt, that someone else had invested in my work. And over the weeks that I was there I became more and more embroiled in the world of my writing, I almost inhabited it, hardly thought of anything else – which I think is the real value of residencies. Some of the essays in Small Acts of Disappearance were written during – or as a direct result of – other residencies, in Berlin and in Wagga Wagga, and I’m incredibly grateful for both.

Stella: How do you know when an essay is finished?

Fiona: It never is and that is precisely the problem. There’s always something that you could change or refine and it’s very hard to know when it’s time to let go. One of my university colleagues once described this process to me as balancing out perfectionism with pragmatism, and as a stubborn perfectionist, I’ve clung to this phrase ever since. Once I notice that I’m mostly just rearranging words, and adding and subtracting commas, I know it’s time to stop. I then leave the essay aside for a week or so before revisiting it with fresh eyes, just to be safe.

Stella: Do you have a favourite book written by an Australian woman?

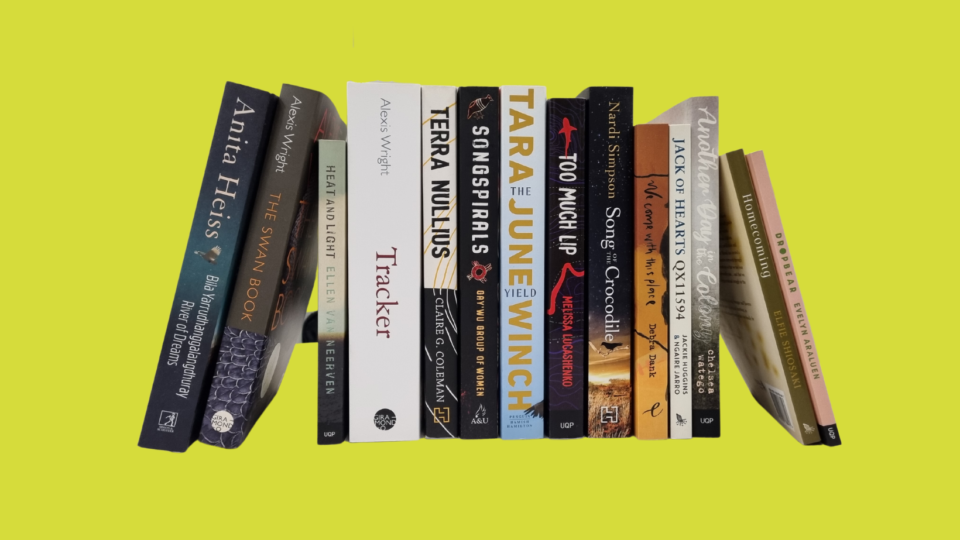

Fiona: I have so many. My bookshelves – and I know this is unusual – are actually occupied predominantly by books by Australian women. I didn’t set out to do this on purpose; it’s just the kind of writing that I love most and this is one of the reasons why I’m so glad that the Stella Prize exists.

One of my favourites, though, is Beverley Farmer’s The Seal Woman. It’s not one of her better-known works but it’s a gorgeous, melancholy novel about a woman living beside a wild and often broiling beach. She falls in love with a man who doesn’t really love her in return. I was in my very early twenties when I read it and was constantly falling for aloof, elusive and very charming people who were utterly unavailable and unattainable, and the book really helped me feel less alone in that. I still think that’s one of the most powerful things any book can do.

Stella: What inspired you to write Small Acts of Disappearance: Essays on Hunger?

Fiona: I wrote the first essay in Small Acts just after my first admission to a hospital day program, just over four years ago now. It was an experience that really shook up what I thought I knew about myself; about the stories I had told myself about my life and my world and, as a result, I was left sort of sifting through, re-examining the pieces and trying to make sense of them again. The essay form proved to be ideal for this kind of thing because it really allows a thinking-through without forcing conclusions or clean narratives.

As the collection grew, I became more and more interested in the relationship between hunger and writing, as systems for ordering and making meaning, and as very different kinds of striving and expression. I wanted to understand these connections, and to explain myself too, I think, and the book really grew out of this process.

Stella: Which aspects of the writing process do you find to be the most challenging and the most rewarding?

Fiona: I think honesty – hard and often-ugly honesty – is the most rewarding aspect of writing, and of reading, but it’s one of the most difficult things to do, too. Writing honestly about difficult and complex things, I think, leaches them of some of their poison, if only because it means you can see them clearly and put them to some kind of use. This is true of fiction and poetry as well as nonfiction. I think it’s honesty – literal, metaphorical or otherwise – that really allows for connection in writing.

On a more practical level, I find pacing and plot very challenging, probably because of my background as a poet – plot, in particular, is not important to that form! I’ve had to find ways to work around this, but always have to work very hard to hit the right balance between narrative and poetic logic; between driving progression through plot and through suggestive connections. It’s tricky, but it’s utterly exhilarating when it’s falling properly into place.