A Tribute to Georgia Blain and Between a Wolf and a Dog

Tegan Bennett Daylight

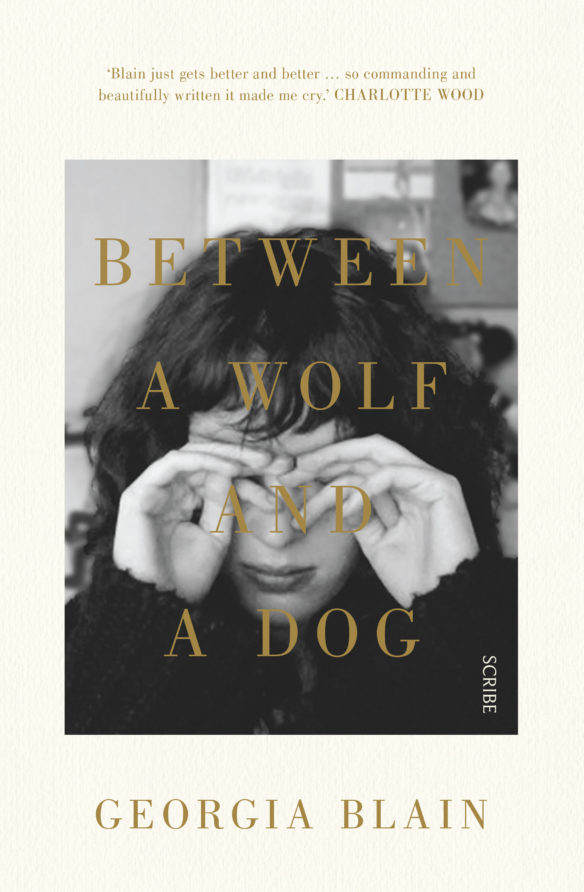

Georgia Blain’s final novel, Between a Wolf and a Dog, was published in 2016 and is currently shortlisted for the 2017 Stella Prize. Sadly, Georgia passed away from a brain tumour in December 2016. To honour her shortlisting and celebrate the novel, Georgia’s friend and fellow writer Tegan Bennett Daylight shares this reflection.

The last time I was with Georgia we were coming home from lunch with our friend Charlotte Wood. The car was full of the quiet sounds of two people settling themselves; us clicking our seatbelts, Georgia pulling her bag on to her lap, me turning the key in the ignition, putting the windows down to cool the interior. We were talking about writing, and Georgia said, ‘These days, I think it’s just about telling a story.’

‘Like Rosie’s work,’ I said. ‘When I started reading her, it felt like I started to notice stories. How nice it was to be told a story.’

‘Exactly.’

We were talking about the writer Rosie Scott, Georgia’s closest friend, who saw Georgia through many books. She was Georgia’s first reader and second mother, gentler perhaps than Georgia’s complex, clever mother Anne.

‘She’s modest,’ said Georgia as we drove up Juliett Street. ‘She just wants to stay in print. To tell stories.’

These are painful words to write because they recall so vividly the feel of those days – bright and clear, warming up for a terrible summer that Georgia wouldn’t have to endure. The conversation with Charlotte at the café was still in the air around us, the talk about our usual stuff – writing, writers, people and their folly, our husbands and our children, and Georgia’s impending death. You knew not to be a chicken when you were with Georgia, because she was one of the bravest people you’d ever meet. You knew what she was facing, and that any terror or discomfort on your own part had to be overcome, in order to make the space for Georgia to say whatever she needed to say.

When I re-read Between a Wolf and a Dog for this piece I was returned immediately to the two of us in the car, talking, that simple corporeal there-ness that becomes so hard to let go of when a friend dies. And of course I’m returned to the idea of story. I’m sorry to say that the first time I read Between a Wolf and a Dog I did so too quickly, my eyes sped along the lines by grief and fear at what I would find. I was a chicken. I couldn’t take it in properly. I knew too much about it.

When I re-read Between a Wolf and a Dog for this piece I was returned immediately to the two of us in the car, talking, that simple corporeal there-ness that becomes so hard to let go of when a friend dies. And of course I’m returned to the idea of story. I’m sorry to say that the first time I read Between a Wolf and a Dog I did so too quickly, my eyes sped along the lines by grief and fear at what I would find. I was a chicken. I couldn’t take it in properly. I knew too much about it.

But this time I’m reading it for pleasure. Of course, the people in Between a Wolf and a Dog are all suffering in some way. It’s not just Hilary, who has a brain tumour and has to make a choice between living until she dies from it, or choosing to die – there’s Ester and Lawrence, whose marriage has broken up; there’s April, Ester’s sister who has committed a crime against sisterhood that can’t be forgiven; and there are Ester’s clients in her psychotherapy practice, all fighting their way through unhappiness. It’s in many ways a sad book. But sadness is not the point. This is a story. You really want to know what happens, and you can feel the riddle of each character moving closer to solution as you read. The book brings you deep satisfaction as well as tears. It’s the work of someone who’s spent a lifetime writing fiction.

We’d wound down our talk about writing and we were talking about our thought patterns, the way certain painful ideas could lodge and be difficult to shift. I asked her if anything was preoccupying her at the moment, and she sighed and said, ‘No. Just saying goodbye.’

Georgia was pressed by circumstance into these exchanges time and again. She hated false profundity and sentiment, and she would hate it if I pretended that we had shared something very remarkable at this moment. She was only interested in the truth, and would have laughed or snarled at the neatness of this ‘final memory’ of her. Georgia’s writing was about people close up, the truth of an exchange like this one, the inadequate way we are in the face of death. I’m glad that the Stella Prize recognises writing by women. I’m even gladder that it recognises this – that many women write about the domestic, and that this is not always valued, or treated as equal beside the books that tackle what some might call more important issues.

We kept driving, and talked about Odessa, and Andrew, and her new book that will be published this year. We pulled up at her house. The sun shone, there were new leaves on the trees, her dog – ‘the only one in this house who carries on like a pork chop’ – barked at me, and she gave me a quick kiss on the cheek. We planned to catch up again soon, and though we wouldn’t do that, we texted jokes, banalities, and some messages of love until a few days before she died.

Tegan Bennett Daylight is a teacher, critic and fiction writer. Her story collection Six Bedrooms was shortlisted for the 2016 Stella Prize. She is the author of several books for children and teenagers, and the novels Bombora, What Falls Away and Safety. She lives in the Blue Mountains with her husband and two children.

Tegan Bennett Daylight is a teacher, critic and fiction writer. Her story collection Six Bedrooms was shortlisted for the 2016 Stella Prize. She is the author of several books for children and teenagers, and the novels Bombora, What Falls Away and Safety. She lives in the Blue Mountains with her husband and two children.