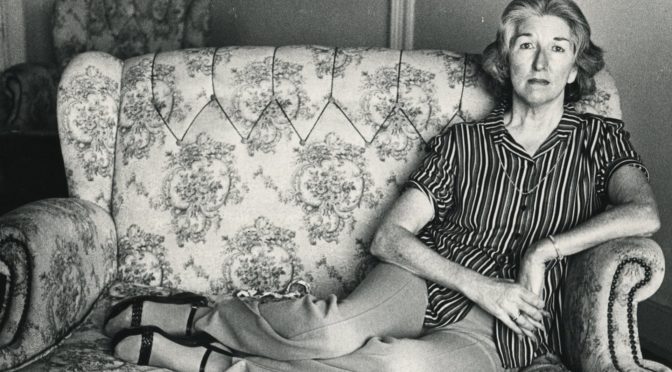

A Tribute to Elizabeth Harrower

Elizabeth Harrower’s collection of short stories, A Few Days in the Country, was shortlisted for the 2016 Stella Prize. Elizabeth passed away this year at the age of 92. In memory of Elizabeth’s writing life, fellow writer Susan Wyndham reflects on her career and the lasting impact of her books into the future.

Elizabeth Harrower was 68 and had not published a novel for 30 years when she won her first and only literary prize. The Patrick White Award was set up by her friend White with his Nobel Prize money for a writer “who had not received adequate recognition”. She emphatically agreed that she was a deserving winner in 1996.

“I thought I was going to hold the unique place of an Australian writer who had a lot of good reviews but never won an award,” she told me in a telephone interview at the time.

I regret not making an effort to meet her then. Although I was a newspaper literary editor and had studied Australian literature at university, I had not heard of Harrower. There were academic admirers and reprints of some novels, but the award still did not bring her into proper prominence.

After her death in July at the age of 92, I joined some of Harrower’s oldest friends to remember her over champagne and high tea at Sydney’s Queen Victoria Building, where as a young woman she had read her way through the public library. One friend speculated that her life would have been different if she’d won the Miles Franklin Award in 1966 for her fourth novel, The Watch Tower, which still stands as a masterpiece.

Instead she lost heart, despite White’s nagging and two Australia Council for the Arts Literature Board grants, and after her mother’s death in 1970 she gradually stopped writing.

The Harrower Renaissance came almost two decades later when publisher Michael Heyward brought her four novels back into print as classics. He persuaded her to allow publication of a forgotten fifth novel, In Certain Circles, which she had withdrawn from an ambivalent publisher in 1971. It was a finalist in the 2015 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards.

Heyward compiled her short fiction into a collection, A Few Days in the Country and Other Stories, shortlisted for the Stella Prize in 2016. It would have been hard to beat that year’s Stella winner: The Natural Way of Things by Charlotte Wood was a fierce dystopian cry against misogyny, an uncannily well-timed reiteration of Harrower’s theme of women trapped in suffocating and abusive relationships.

Harrower poured out her intense dramas, at her most driven during eight lean years in London, always while doing other jobs. Down in the City (1957), The Long Prospect (1958), The Catherine Wheel (1960), The Watch Tower (1966) were written in pre-feminist times when societies were scarred by Depression and wars. She wrote her short stories across those years and into the 1970s, as the world was changing rapidly but human nature less so.

Rereading A Few Days in the Country recently, I held my breath again at the clarity of her writing about toxic relationships in microcosm. Adults and children are crushed by petty tyrants who are lovers, husbands, parents, bosses or friends. Oppressors are sometimes oppressed by their own hardship or illness.

History sits just off-stage. “No one in that town could have ambitions beyond not being hungry,” says the daughter of a social whirlwind in Alice. Class swings the scales as much as gender. Social and intellectual snobbery are weapons. Powerless women manipulate their victims with jealous intimacy.

Books give solace to some of her quiet sufferers. In The Beautiful Climate a moody, possibly bipolar, father forces Del and her mother to spend weekends in the prison of an island cottage. She is saved by finding the former owner’s mould-spotted books:

“Normally, in an effort to find out why people were so peculiar, she read nothing but psychology. Even after she knew psychologists did not know, she kept reading it from force of habit in the hope that she might come across a formula for survival…Poetry was a change.”

Harrower had considered studying psychology in London but decided she could learn more by reading history and observing people, which she did with laser eyes. As a writer she was knife-sharp and nuanced, with sympathy for underdogs but no literary mercy.

I finally met Harrower six years ago, for another interview as In Certain Circles appeared. Buoyed by the late celebration of her work, she was gracious and sociable. From then on we met occasionally at her apartment, where I looked down on the boats of Sydney Harbour while she served coffee, pastries and the wisdom of a woman my mother’s age.

We didn’t much talk about her books, which she had no interest in revisiting after 40 years, and I tried not to gush about their greatness. Where her cool dark fiction came from, she never really revealed. She spoke of a difficult childhood when she “never saw any happy marriages” and said, “I’ve had every experience and I’ve behaved every which way. I like people so much.”

We did talk about being “divorced children”, our late mothers, our love of Scotland where we had family roots. She reminisced about friends, many of them gone, and political heroes Gough Whitlam and Clement Attlee, who was the British Prime Minister when she arrived in London and shaped her strong political views. We talked about books, of course, and I gave her a new biography of Attlee, which she read quickly and admired. Like all her friends, I feel we had much more to discuss.

Through her long silence Harrower quietly believed her books were good and would be published again after her death. How much better that she lived to see them reborn. May they have the long life they deserve.

Susan Wyndham is a journalist, writer and former literary editor of The Sydney Morning Herald.