The Stella Interviews: Eloise Grills

Congratulations on being longlisted for the 2023 Stella Prize! What does it mean to you to be included on the list?

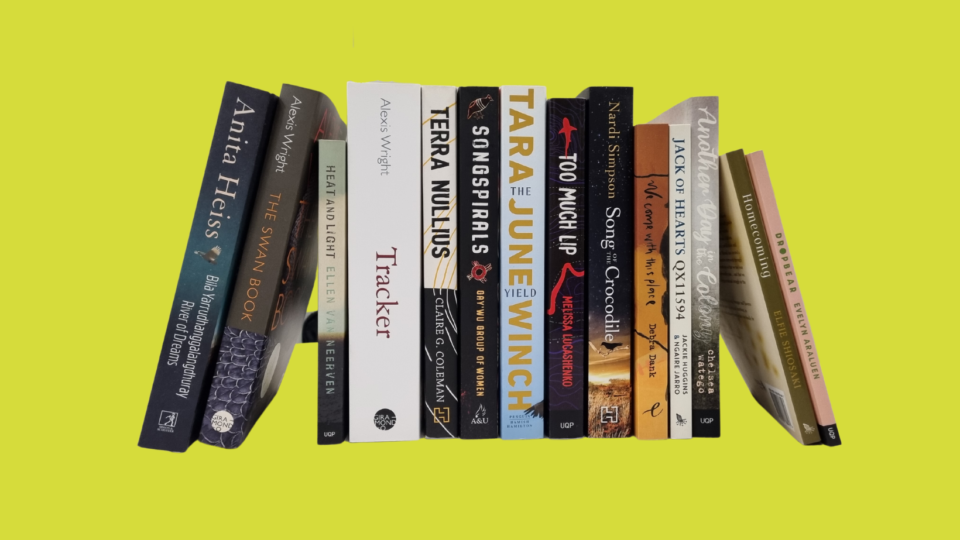

It’s an incredible honour. Some of my favourite books of the last few years have either been shortlisted or won the prize (Dropbear by Evelyn Araluen was a huge artistic influence on me when creating big beautiful female theory, and so is the work of Maria Tumarkin, Ellena Savage, Lee Lai and Mandy Ord, to name just a few).

The Stella is such an exciting award in that it champions work of writers who have historically been excluded from the literary world. I’m also really impressed by the prize’s evolution in the last few years to encompass a range of forms (not just fiction and non-fiction, but poetry), and was so excited by the experimental, poetic and genre-defying work that was shortlisted last year.

Basically, being on this longlist is a huge bucket list item of mine, and at the age of 33.5 ish, I am now ready and happy to die (joke, joke).

Your longlisted book, big beautiful female theory, has been described by Declan Fry (ABC) as “part comic book memoir, part prose poem, part manifesto”. How do you explore and challenge form in your work?

It’s perhaps not so much of an intentional challenging as a matter of what I’m interested in as an artist, what I enjoy, and how I wanted to throw all these desires, artistic interests and unwillingness to be bored into this collection. I’m very much of the philosophy that form should be married to content, in some way, and thus I am never very happy with a piece until I have found a form with an affinity for what I am trying to convey—either matching the mood, or the feeling, or the progression of ideas.

For instance, when I was writing the final essay of the collection, Huge sweeping meaninglessness of life with human body, for scale, I was exploring the notion of the confessional in writing and its historically specific and gendered nature in our culture, and eventually (through many drafts) fitted it to the form of the Medieval illuminated manuscript.

This form connotes ideas of confession and religious practice, and I felt this had an affinity with the dogmatic nature of the confessional mode. Also, the monk’s illustrations in these texts often introduce idiosyncratic double-meanings, expressing the scribe’s opinions, and interrupting or elaborating on or satirising the rest of the content. Often what I’m trying to do when illustrating my work is to introduce a similar disruption, so I felt that the spirit of this tied in nicely to the ideas of my essay.

What are some of the central ambitions and themes of your book?

I wanted to convey the sexy everyday tragedy of living in a human body, especially a fat human body, especially a fat human woman’s body.

I aimed to try come to terms with my own experience, and to make other people who might have had similar feelings of self-hatred, ambivalence or dissociation form their bodies feel less alone. The book is interested in the bodymind as impacted by diet culture, gendered expectations, beauty, and other societal pressures, and how we can not just live but thrive through defiant self-acceptance and untempered expression.

I also love the idea of writing as a kind of weaving, or quilting. In latin, the word text is derived from the past tense of the Latin, textus, which is a form of past tense of texo, ‘I weave’. I bring this up not to prove that I am some kind of rabid dictionary fanatic (the zebra did it) but, historically, of course, women have been aligned with quilting and other forms of textiles as societally approved forms of expression.

As such, I wanted the book to be a kind of literary quilt, weaving together disparate ideas, textures, experiences and imagery to convey what it feels to live inside a contemporary brain, a body, a culture and society.

I wanted to convey the sexy everyday tragedy of living in a human body, especially a fat human body, especially a fat human woman’s body.

Can you tell us a bit about your artistic process? How do you write, where, when, and on what?

I’m not someone who does the Artist’s Way and gets up each morning and does their pages. I tried it and I found it just boosted my toxic tendency toward perfectionism. I’m much more interested in having a creative approach to the structure of my days now, rather than the narrow, restrictive pattern my inner critic is comfortable with.

I favour an open-ended approach, and have many ways of ‘writing’. I am lucky in that I have an art practice as well as a writing practice, and so these forms speak to one another and feed each other and help me with my creative production in general. I like to change it up between forms to ensure that I am not bored, rotating between reading, writing, drawing and painting through my week.

Most of my formal writing is done at my desk, but I often have my best insights and come up with my best ideas and lines when I’m in motion. I always bring my phone with me on a walk and I use a notes or a docs app on my phone to take quick impressions. I would use a notebook but I find that my writing is so much faster when I type and I can keep up with my brain that way. Taking photos, reading, walking, snacking, napping—I have so many ways of writing, many of which look like doing nothing at all.

What’s on your reading pile at the moment?

I am halfway through Mary Ruefle’s incredible collection of poetry-essays, Madness, Rack and Honey. I’m currently reading The Idiot by Dostoevsky (I’ve been reading this book, off-and-on for three years), and a collection of Patricia Highsmith’s short stories. Also, Red Comet, the big fat biography of Sylvia Plath, by Heather Clark. And the recently translated graphic memoir by Belgian artist, Dominique Goblet, Pretending is Lying. As you can probably tell, I read broadly and vociferously, between forms, genres, and eras. I often am midway through too many books at a time, diving in and out, finding little bits of inspiration in each and (hopefully) braiding these gleaned insights into my own writing and art.

Find out more about Eloise Grills’ 2023 Stella Prize longlisted book, big beautiful female theory.