Evelyn Araluen’s 2022 Stella Prize Acceptance Speech

Jingiwalla.

It is important for me to begin my response to this incredible honour by paying my respects and reverence to the immemorial custodians of this land, the Wurundjeri peoples of the Kulin Nation. I am grateful for their ongoing care of Country, and for that of the broader Kulin nation. Their sovereignty stands at the heart of everything we talk about tonight. I’m grateful to have been a guest on this Country these last two years: this place has provided me with safety and community, as it has done so for many generations of Aboriginal people from other nations for decades. For years I’ve heard sovereign Blak women in the Victorian Aboriginal community speak of the erasure of their work by outsiders, and as such I don’t step into this place neutrally simply by virtue of being an Aboriginal woman. This is stolen land; and this is sovereign Country.

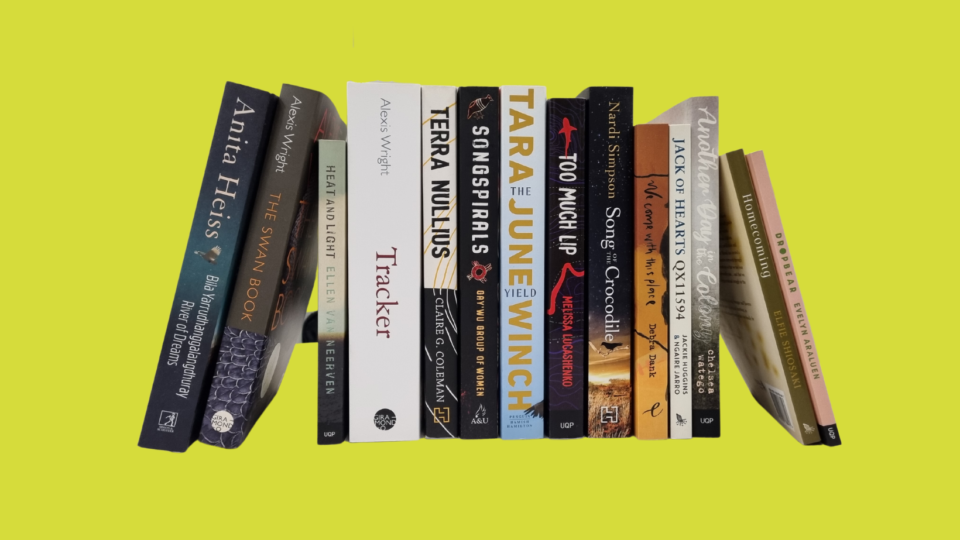

It’s an astonishing honour to be standing here before you tonight to accept this prize. Given such a brilliant and formally ambitious list, in such an incredible year for publishing, I really didn’t think Dropbear would get a look in. I wrote a strange little book which began with the experience of rattling through my dad’s shed to remind myself of the stories I’d grown up with. It’s beyond comprehension for me to see it here alongside phenomenal works of political critique, such as Chelsea Watego’s Another Day in the Colony, or beautifully lyrical interweavings of history and culture such as Elfie Shiosaki’s Homecoming.

I wrote this book from a place that was centrally moved by the work of women within, against, and beyond the archive of the settler colony. Every opportunity, every prize, every publication, every success of my career has borne the touch of women, but especially Blak women, and they have made my presence here possible. The landscape I work in was built by their energy, and in many cases, their sacrifice. I’ll spend my life searching for ways to thank them for what they’ve given to generations of storytellers like myself – far more than can ever be distilled in one speech.

That said, I was always taught that care of Country was about reciprocity, that we care as others have cared, we seek to provide what has been provided.

So standing here tonight with this great honour, in a room full of such distinguished people I’d like to take a moment to speak about the urgent necessity of proper funding for the arts.

The last two and a half years have demonstrated the power of mutual aid in crises, and the clear, tangible, and irrefutable social benefit provided by the arts community. From the AuthorsForFireys campaign, in which Australian writers auctioned their books to raise over half a million dollars for bushfire relief and recovery, to the time when the Koori Mail lead widescale disaster relief across flood-devastated Bundjalung Country, providing food, blankets, medical supplies and even a place to sleep for stranded families. And all this while the police camped outside devastated communities with speed traps, booking drivers for overdue registrations. Our arts sector is punching well above its weight for mutual aid, advocacy for human rights, and the environment, and as a voice for fundamental human dignity. But, as we all know, the arts are only sustained, barely sustained, by unpaid labour. By the struggle and sacrifice of artists and arts-workers who accept punishing and finally untenable working conditions for love and passion.

To speak from my own experience for a moment, one year ago I was about as broke as I’d ever been. I was a published author, I was working two jobs, I’d gone to university and moved 900kms away from my family in search of better economic prospects, and my partner and I were living in incredibly strained circumstances. At the start of the pandemic our incomes halved in an instant. We lost teaching, we lost events, we lost contracts for projects we’d spent months, even years building towards. Most postgraduates or early career researchers we knew dropped out or retrained once it became apparent that the university sector, where so many artists are employed as educators, would not be included in federal or state support initiatives. When the terms of those support packages were re-written four times to exclude tertiary education, while already wealthy corporations pocketed millions of tax-payers dollars. When artists were told we could drain our already scant superannuation funds to keep us from ending up homeless.

I doubt we’ll ever know how much the arts lost during these last few years.

Artists, in this country anyway, are used to instability, we’re used to two or three jobs, we’re used to paltry super, and the constant fear of illness and accident faced by all precarious workers. We’re used to living one paycheck away from poverty. Despite this slap in the face, this blunt dismissal of the clear social and cultural good the arts provides to all Australians, artists were still advocating and organising throughout the pandemic, and the fires and the floods. They were still working through the isolation of endless lockdowns in the hope that their creative efforts, their work, would help someone else survive.

This is not sustainable, and it never has been. This structure produces mass inequality of representation and will continue to restrict access for creatives from working class and marginalised contexts. We can do better than this: we can build diverse, democratic, and vibrant arts and education cultures with a dignified basic income, with long-term stable funding for community organisations and professional development programs, with bargaining codes and consultations and policies to protect our rights and safety. We can do this collectively. We can mobilise our arts sector and let artists and educators do what they do best: make art that speaks truth to power, that bears witness to suffering, that demands justice.

I am honoured to win this prize, I truly am. It means my partner and I can pay our HECS debts, can spend time back home with our loved ones, can scale down from three to two jobs and for a while at least have something like a weekend. I don’t want the dignity and the peace this prize provides to be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for a handful of the lucky ones though. If you hold legislative influence, if you work in government or in philanthropy or in a position of other influence I beg you to think of the responsibility you bear to your community, and the influence you might lead. The arts are also our Country, and I beg you to care for it. Stepping off my soapbox… I am so grateful to so many people who have made Dropbear and my being here possible. Thank you to the Stella Prize, to the judging panel, to the supporters, and sponsors. Thank you to the Blak people in the room: whether you be writers or advocates or teachers or my family. Thank you for being Blak and deadly. I am blessed to be guided by the incredible wisdom of Blak women, Jeanine, Sheelagh, Melissa, I watch how you work and lead and I’m constantly humbled by it. Thank you Ellen van Neerven for taking my hand with this story, Aviva and the UQP crew for transforming it into what it has become. Thank you forever and ever and ever to my parents and my family. I adore you. Last, but never, never least: Jonathan.

– Evelyn Araluen, winner of the 2022 Stella Prize for Dropbear