The 2022 Stella Prize Judges’ Report

Ironically, in a year when the pandemic has meant international (and some domestic) borders remain closed to most Australians, the Stella Prize has ranged further afield than ever. A distinct outward-looking flavour characterised the pool of 220+ entries. Many authors focussed on global affairs rather than on the Antipodean alone; much of the short fiction and poetry we read was set offshore, and at least two of the longlisted authors are Australian expatriates. So much for Fortress Australia.

The most obvious difference in 2022, though, has been the inclusion, for the first time, of poetry as an eligible genre. Of 227 entries, 38 were collections by poets. Four of the most outstanding of these have been longlisted. Many other powerful and appealing poetic voices inevitably fell by the wayside, in what has been an exceptionally strong year.

The nonfiction longlistees can be broadly summed up as both intensely thoughtful and fiercely outspoken. In the aftermath of Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, Stella writers are not holding back. These authors have married sharp analyses of particular issues – being young and Muslim in an age of toxic Islamaphobia; living in a neocolonial state which continually fails to recognise the rights of First Nations; grief for a lost companion in a world wracked by larger losses and wrongs – with an exhilarating boldness.

Five works of fiction make up the remainder of the list. We were delighted to include a compelling graphic novel in our longlist. This depiction of queer lovers struggling with difficult obligations to family and to each other is innovative in both form and content, as well as being an extremely enjoyable read.

Two incisive short fiction collections by relative newcomers impressed with their mastery of craft so early in their authors’ writing careers. Both the novelists chosen are, in contrast, already well-established as important Australian literary voices, and both are writing characters normally seen as marginal – foster children and rural Aboriginal people respectively. Notably, the longlist includes one of a very tiny handful of recent novels centering Aboriginal love – a quietly revolutionary narrative.

Australian women and non-binary writers are producing innovative, sophisticated literature in very difficult times. It has been a great privilege to read and assess their work for the 2022 Stella Prize.

– Melissa Lucashenko

Chair of the 2022 Stella Prize Judges

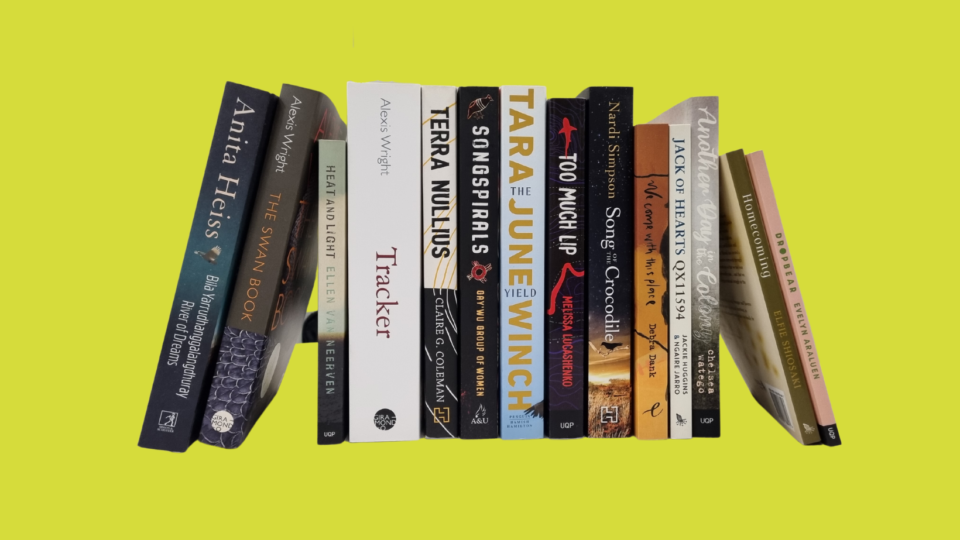

The 2022 Stella Prize longlist

Coming of Age in the War on Terror by Randa Abdel-Fattah (NewSouth Books)

TAKE CARE by Eunice Andrada (Giramondo Publishing)

Dropbear by Evelyn Araluen (University of Queensland Press)

She Is Haunted by Paige Clark (Allen & Unwin)

No Document by Anwen Crawford (Giramondo Publishing)

Bodies of Light by Jennifer Down (Text Publishing)

Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray by Anita Heiss (Simon & Schuster)

Stone Fruit by Lee Lai (Fantagraphics)

Permafrost by SJ Norman (University of Queensland Press)

Homecoming by Elfie Shiosaki (Magabala Books)

The Open by Lucy Van (Cordite Books)

Another Day in the Colony by Chelsea Watego (University of Queensland Press)

Coming of Age in the War on Terror by Randa Abdel-Fattah

Randa Abdel-Fattah was inspired to write this book after a young Muslim boy told her that school was no longer “the one place he felt safe.” In this searing analysis of state incompetence and abuse, she weaves academic ideas with the real-life experiences of children of the 9-11 generation, both Muslim and other. Now approaching adulthood, the young Muslims she speaks with are mostly interested in Netflix and passing their exams, but they also know they are the imagined ‘bogeymen’ by governments and Islamaphobes all over Australia.

In a radical departure from the norm which systematically silences such students, Abdel-Fatteh has chosen to interview, and take seriously, teenagers from a range of class, religious, ethnic, and school backgrounds. The portrait which emerges from her study is one of manufactured fear, staggering ignorance on the part of some schools and governments, and a generation of young Muslim Australians who’ve grown up understanding that their ‘belonging’ here is always provisional. Coming of Age in the War on Terror is urgent and compelling storytelling.

TAKE CARE by Eunice Andrada

Eunice Andrada’s second poetry collection meditates on the ethics of care and the need to dismantle in order to recollect, to recover, and to create. Andrada is a master of final lines, and many of these poems – ‘Subtle Asian Traits’, ‘Duolingo’, ‘Pipeline Polyptych’ – conclude with memorably succinct and inspired turns, as in the sardonic humour of ‘Don’t you hate it when women’, which goes from “kill the herbs on the windowsill /devote their year’s salary to take-out” to “kill the cop / the colonizer / the capitalist / living rent-free in their heads / demolish the altar built on their backs / without blame /walk away”.

Andrada’s collection adroitly combines the personal, the political, and the geopolitical, narrated by a voice that is at once hip, witty, and deeply serious. Andrada has the imaginative ability to move between the memories of poet-narrators, historical asides, reflections on the nature of race and feminism in Australia, and questions of colonisation both locally and in the Philippines. Formally remarkable, stylistically impressive, and often surprising, TAKE CARE is a collection that understands the ways in which “There are things we must kill / so we can live to celebrate.”

Dropbear by Evelyn Araluen

Dropbear is a breathtaking collection of poetry and short prose which arrests key icons of mainstream Australian culture and turns them inside out, with malice aforethought. Araluen’s brilliance sizzles when she goes on the attack against the kitsch and the cuddly: against Australia’s fantasy of its own racial and environmental innocence. She revels in difficult questions like “Can’t be lyric if you’re flora, right/Can’t be sovereign if you’re fauna, right?” And “Humans…did you really think all the Bad Banksia men were deadibones when they went to the bottom of the sea…?”

Acerbic, witty, and with no reverence at all for the colony, Araluen remembers those dispossessed and voiceless, just as she predicts a hard-won future for her children – “look at this earth we cauterised/the healing we took with flame/I will show them a place/they will never have to leave”.

She Is Haunted by Paige Clark

Sometimes a new literary voice seems to spring almost fully-formed onto the page, and this is the case with writer, researcher, and teacher Paige Clark, in her arresting and confident debut collection. Featuring an array of protagonists who are almost all women caught in moments of unease, uncertainty and transformation, Clark’s assured, inventive voice never wavers as she moves across eclectic, strange, and sometimes surreal subject matter.

From the opening story which crackles with mordant wit and urgency as a pregnant woman makes breakneck bargains with a smug, unpredictable God about her unborn baby, to the nuanced ‘Times I’ve Wanted to be You’ where a newly-widowed woman begins to wear her deceased partner’s clothes in an attempt to deal with grief over his loss, Clark expertly threads together fractured lines of intergenerational, transnational, and diasporic identity, as well as satirical takes on the flattening coldness of bureaucracy and the minefields of mother-daughter relationships, and female friendships.

If this is what she can do with her debut work, we can’t wait to see what she writes next.

No Document by Anwen Crawford

No Document is a longform poetic essay that considers the ways we might use an experience of grief to continue living, creating, and reimagining the world we live in with greater compassion and honour.

Reflecting on the loss of a close friend, comrade, and creative collaborator, Crawford moves through time in search of a remembered momentum towards revolution. Deconstruction and creation exist side-by-side as the processes of artistic techniques are described in detail, as well as the successes and failures of collective action.

This work is a complex, deeply thought, and deeply felt ode to friendship and collaboration. There is the persistent feeling that through grief – remarkable and devastating – one is able to temporarily glimpse everything they need to know. Returning to something lost is full of sadness, futility, and frustration but also represents a fierce commitment to possibility. The emotional, paradoxical tumble of grief and hope represents a universal desire for meaningful change and No Document implores us to harness that desire collectively.

Bodies of Light by Jennifer Down

Told with a kind of conversational intimacy – inviting the reader in, rationalising, second-guessing, accounting, defending, justifying – Jennifer Down inhabits the voice of a woman who has experienced a great deal of trauma, while evoking a history of south-east Melbourne from the 1970s into the present. Down shows restraint in detailing the traumatic circumstances of her protagonist Maggie Sullivan’s history – including foster homes, child sexual abuse and drug addiction – employing a language that moves between forensic accounting and a more lyrical, authorial register (“Picture me in that summer slick, newly fifteen and in search of a hollow to fall through”). Down’s portrayal of Maggie’s joys and pains evinces an impressive degree of verisimilitude and sensitivity, and many of the other characters – Judith, a middle-aged carer, and Ned, Maggie’s one-time boyfriend – are memorably drawn.

This is an ambitious novel, spanning decades and locales, that sees Down demonstrate her imaginative range and take risks following the success of her previous two books. The result is a daring and compelling work, suffused with pathos and an impressive degree of empathic vulnerability.

Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray by Anita Heiss

Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray is inspired by the true story of Wiradyuri men – Yarri and Jacky Jacky – who saved the lives of sixty people during a flood that took place in 1852. It places the remarkable fictionalised story of Wagadhaany at the centre, allowing her sensitivity, grit, and strength to shine through on every page.

Anita Heiss’s novel is written for all ages, and has a timeless quality, and yet it grapples with complex material, presenting an extraordinary portrait of what it means when a white woman’s desire to be seen as ‘good’ outstrips her loyalty to her Black friend. Heiss explores the contours of good intentions without bitterness or rancour. With a keen eye for detail, Heiss writes with poignancy and tenderness about Wagadhaany’s love affair and her journey to motherhood. In charting Wagadhaany’s struggles to keep her family together, and return to her home in Gundagai, Heiss has created a new national heroine.

Bila Yarrudhanggalangdhuray belongs in the library of all Australians, no matter their age. Heiss has chronicled the story of one woman’s fight to maintain her dignity in a dramatically changing world. In so doing, Heiss has written a story for her people certainly, but she has also written a story for the nation.

Stone Fruit by Lee Lai (Fantagraphics)

Lee Lai’s Stone Fruit is a moving graphic novel in which queer couple, Bron and Ray, find themselves at a tense crossroads in their relationship. Mental health struggles and wounds inflicted in their families of origin have brought their relationship to a heartbreaking impasse. But amidst this turmoil, their days spent taking care of Ray’s niece, Nessie, are idyllic and imaginative and suggest a future worth moving towards. Throughout scenes rendered in Lai’s signature art style – simple lines and a muted blue and grey colour palette – and featuring spare, perfectly articulated dialogue, Bron and Ray go looking for answers about how to heal these past hurts in order to show up better for each other as a couple. Stone Fruit beautifully reflects a tender domesticity that is affecting and atmospheric.

This is a deceptively simple depiction of the many various and complicated versions of familial love and care we can experience in our lives. Stone Fruit is a work that is honest, unassuming, and powerfully told.

Permafrost by SJ Norman

SJ Norman’s narrators are lonely, anonymous figures. Norman’s prose has a rhythm that captures their narrators’ sense of solitude and wry humour, not to mention – as in the poetic, circuitous rhythms that open ‘Unspeakable.’ – travel’s meditative repetitions. The product of a unique, and uniquely original, voice, the stories in Permafrost move at a lateral angle, with an undercurrent of erotic unease, evoking places and experiences in an impressionistic, dreamlike manner. Each builds an atmosphere that stays with the reader. Norman has a real talent for creating a sense of disquiet – as in one of the collection’s highlights, ‘Playback.’ – that is both eerie and restless, and not often found today in fiction.

Permafrost recalls the haunted atmosphere of traditional uncanny stories and gothic narratives, not to mention the politically charged autofiction and dreamscapes of authors like Tove Ditlevsen and Anna Kavan. What makes Norman’s achievement so successful is that their narrative manoeuvres occur without any particularly lurid or explicit affect; in stories like ‘Stepmother.’, the narrator’s anxiety is both absolutely ordinary – the passage from childhood to pubescence – and yet entirely nightmarish, too.

Homecoming by Elfie Shiosaki

Homecoming is both a genre-defying book, and a deeply respectful ode to the persistence of Noongar people in the face of colonisation and its afterlives. Elfie Shiosaki writes with a steady – and often invisible – hand, amplifying the voices of people whose words have been buried for too long.

Shiosaki has produced a work of careful excavation. With an extraordinarily light touch on the page, Shiosaki moves beyond authorship, occupying, instead, the liminal space of daughter, caretaker, and choirmaster to a chorus of voices.

Shiosaki has delivered a work of poetic and narrative genius and can be read either as an ensemble of poems or as a single piece that moves seamlessly between the elegiac and the joyful. Homecoming is a gift to the nation, one that works its magic with a quiet grace and an unstinting clarity.

The Open by Lucy Van

The Open is a prose poetry collection that explores the pressures of colonisation and capitalism, and the alienation and dislocation they engender.

Broken into four sections, Lucy Van’s poems speak independently and harmoniously. The motif of doors recurs throughout this collection, but as with all of Van’s imagery, the metaphor is always rich and multi-layered: the hinge of an apostrophe and its implications of possession and ownership, the swing of personal and political history, which interrupt each other and reveal the fallible nature of memory, the contradictions of privacy implied by the permeable boundary of a screen door. Van starts with the familiar, then accelerates and expands on its implications, always taking her reader to a fresh space in which to turn these ideas over in the mind again and again and find new meaning in them.

The back and forth of Van’s collection demonstrates gradually over time the burden of choice. Despite the speed of living that the ongoing colonial project demands, one is still left with the responsibility of making decisions about how to be and what meaning to make in the world. The Open invites an understanding that the privacy and vulnerability necessary in order to make these decisions is complex and fraught.

Another Day in the Colony by Chelsea Watego

Chelsea Watego has delivered a work that is part anthem, part love story. In a series of essays about the difficult – often backbreaking – labour involved in surviving the colonial logics and systems that determine everyday life in Australia, Watego refuses to pander to the needs of readers who aren’t Aboriginal. It is unapologetically written for her community.

Watego’s descriptions of the institutional and physical violence Aboriginal people are forced to endure in contemporary Australia are clear, urgent, and white hot with rage. At the same time, her portraits of moments with family, community, and ancestors are tender, vulnerable, and joyous.

Watego creates a Black intellectual republic through her words. Indeed, this assertion of independence is the foundation upon which her work rests. In marking out this space, free from the gaze of white Australia and the systems it has created, Another Day in the Colony creates its own borders and in this way it is brave, and free.

– Melissa Lucashenko (Chair), Declan Fry, Cate Kennedy, Sisonke Msimang, Oliver Reeson

The 2022 Stella Prize judging panel